Adverse neural tension: A sneaky but common cause of pain for rock climbers.

There’s a type of pain that doesn’t get talked about very often and is often missed by PTs and physicians. They’re not trying to gaslight you. It’s just a tricky diagnosis.

One reason is that this type of pain often feels just like muscle, tendon, or joint pain and is found in the same locations as other common diagnoses. By the time clients come to Rock Rehab, they’ve often seen multiple other providers who haven’t been helpful because they’ve missed this diagnosis. Maybe this is you.

Let’s break it down.

Your nerves aren’t just loose wires floating through your body. They’re wrapped in layers of connective tissue — the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium (wow, big words. You’re so smart, Evan!) — which protect the nerve, help regulate blood flow, and allow it to glide smoothly as you move. When everything’s happy, nerves slide, elongate, and tolerate load just fine.

When they’re not happy? Pain happens.

Adverse neural tension presents a lot like other types of pain in the body: sharp or dull or achy or stretchy. Additionally, this pain can feel burning, tingling, electric, or you can feel a sensitive stretch that crosses multiple joints (example: a stretch in the forearm and the fingers at the same time).

You might feel numbness, pins and needles, or symptoms that show up only in certain positions — like reaching overhead, locking off, heel hooking, or dropping into a deep stem. If your hands fall asleep every night while you’re curled up like a typical climber, this could be the reason.

Adverse neural tension usually shows up for one of two reasons:

Nerve entrapment — where the nerve is mechanically irritated by tight muscles, stiff joints, swelling, or a bulging/herniated disc.

Peripheral nerve sensitization — where the nerve becomes overly sensitive, even without a clear physical pinch.

Central sensitization — the central nervous system becomes sensitized due to personal factors such as stress, anxiety, or the presence of chronic pain.

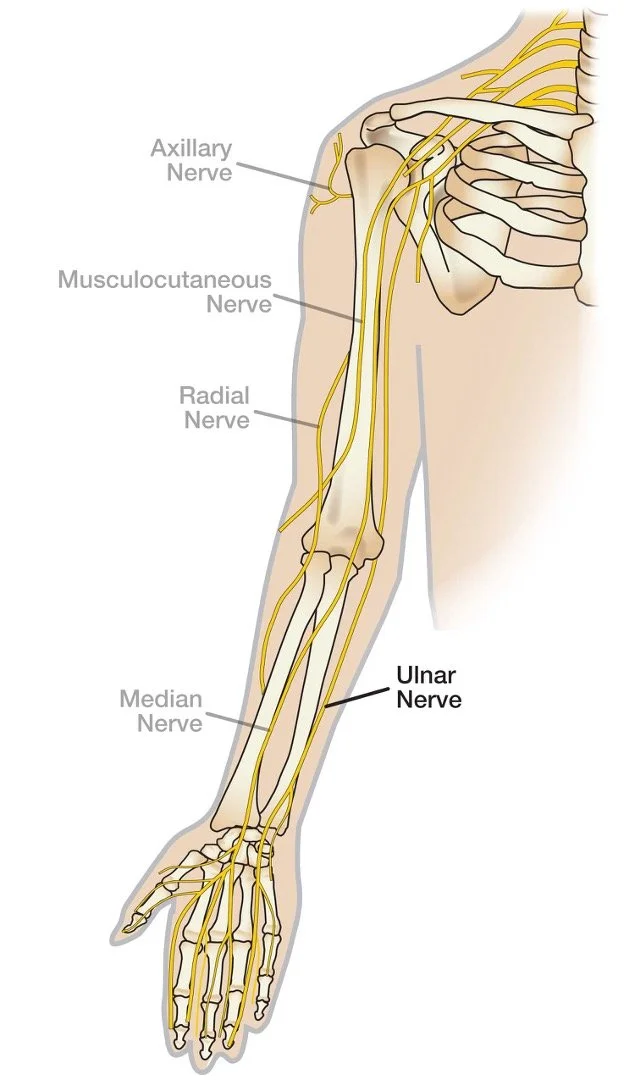

Image credit: https://www.assh.org/handcare/safety/nerves

Climbers are basically a perfect storm for this shit. Common offenders include:

Median nerve (front of the forearm and sometimes into the fingers): caused by repetitive crimping, lock-offs, weighted pull ups.

Ulnar nerve (inner elbow and often into the pinky and ring finger): compression moves, repetitive crimping, lock-offs, weighted pull ups.

Radial nerve (outer elbow/forearm): poor crimping form, repetitive crimping, lock-offs, wrist weakness.

Sciatic nerve (hip/leg/foot): high steps, heel hooks, and drop knees.

So how do we treat this in physical therapy?

First: nerves hate sustained stretching. Long, aggressive holds tend to piss them off even more. Instead, nerves respond best to short-duration, high-volume movement — which is where nerve glides come in.

Nerve glides come in two flavors:

Nerve flossing gently tensions one end of the nerve while slackening the other, then switches — allowing the nerve to move without being pinned down. This is for more sensitive nerves that need to be calmed down.

Nerve tensioning pulls on one or both ends of the nerve without slackening either end. This is a progression for less sensitive nerves, designed to improve nerve length.

Start with nerve flossing. The minimum dosage is 10 reps at a time and our recommendation is 3-5 sets of 15-30 reps, 3-5 times per day, staying below symptom aggravation. If it feels like a stretch you’re trying to “hold,” you’re doing it wrong.

Treatment also includes:

Dry needling or trigger point release to reduce compression and improve tissue mobility

Strengthening to restore tolerance to load

Modifying climbing volume, crimping and grip type, and movement pattern.

Gradually reloading the nerve so it stops acting like an overprotective alarm system

One more key thing: the problem isn’t always where the symptoms are.

Nerves originate in the spine, and issues like disc irritation, joint stiffness, or poor spinal mechanics can increase neural tension downstream. That’s why in PT we often start treating nerves peripherally (where you feel it), but keep a close eye on the neck or low back. If symptoms aren’t resolving, the spine may be the real driver. Cervical spine (neck) and thoracic spine (upper back) dysfunction are common causes of chronic elbow pain because they cause adverse neural tension.

Adverse neural tension is also a very common contributing factor to tennis elbow (lateral epicondylalgia) and golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylalgia)!

Bottom line: adverse neural tension is less about something being “tight” and more about something being irritated or sensitized. It's a signal that something along the nerve’s pathway isn’t moving or loading the way it should. When you address the right driver (whether that’s the elbow, shoulder, hip, or spine) and load the nerve correctly, symptoms usually calm down fast. Ignore it or stretch it aggressively, and it tends to hang around like a bad climbing partner who won’t take a hint.

We take hints. We’re also really good a treating nerve pain. Schedule your appointment at Rock Rehab to get the right diagnosis and a dialed in treatment plan.

About the author:

Evan Ingerson is a Santa Fe, NM–based physical therapist and climbing lifer with over 25 years of experience on the wall and 9 years helping climbers get out of pain and back to crushing. He specializes in climbing injuries, return to climbing plans, and calling out bad beta—on routes and in training plans. Whether you’re tweaked, gassed, or just trying to climb smarter, Evan’s here to keep you sending.